Issue #1: The Basics, and Basic Barricade, Basically.

One of the best things about incorporating theatre games and activities into your teaching is that there are not many requirements for the space in which they are played. No hoops, nets, floor lines, or trampoline floors necessary (though if you've got it, flaunt it!). Theatre games and activities can be played almost anywhere there's flat, open ground: a stage, a classroom (with desks pushed aside to form the playing space boundaries), an outdoor playground, a cafegymnaudiquarium... and believe me, we've played in all these locations and more.

Still, we feel very lucky in our current base of operations, The George Daily Auditorium. The George Daily is a 20-year-old theatre venue located in Oskaloosa, IA. In 1999, the George Daily began its theatre education program, which took various forms until 2013, when Andy was hired as the venue's first full-time Education Director, and the Auditorium began to offer a year-round theatre education program.

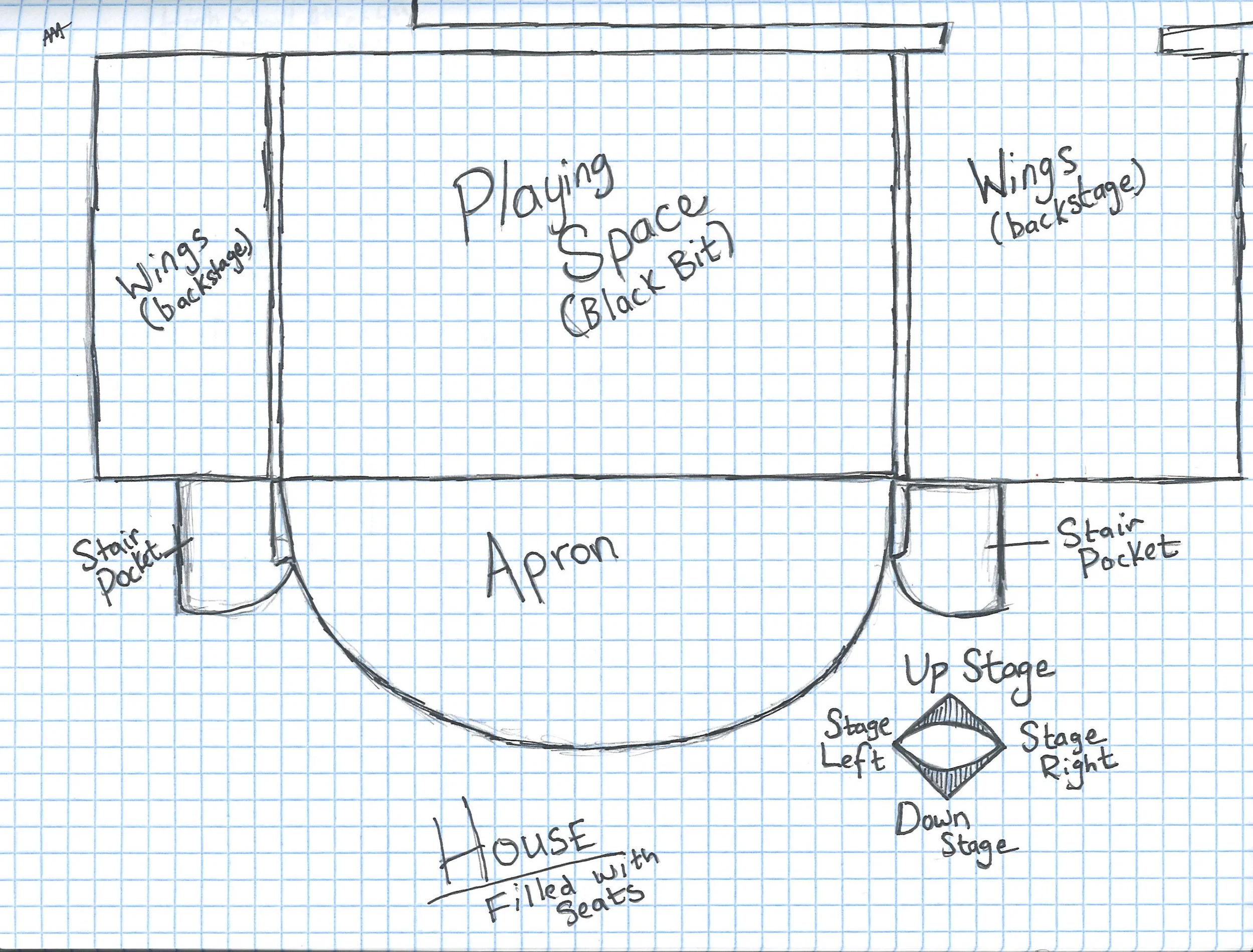

For you visual learners out there, this is the layout of the auditorium, which is where we do the bulk of our playing. However, all of our games can be adapted to fit the spaces available to you. We think you'll find that your space is uniquely suited to some games, while other games will need to be retrofitted.

As you can see, the Youth Theatre has lots of room to play. Just out of view in this drawing is a black box theatre that has the same 49'x31' layout as the main stage, and the front of the building holds a boardroom with the same footprint. The auditorium was designed to have one show on the main stage, with two other shows rehearsing in the black box and board room.

Another great area often used during theatre camp is the "house," or auditorium seating space, with 696 seats in raked rows divided by two aisles. The games we've created to play in the house, like "Shark Attack," show the perks of using the unique characteristics of your space to DYOG (Design Your Own Games). We also use an outdoor football practice field, as well as the lobby and hallway areas, so the bathrooms are pretty much the only places not used for gaming at the Daily.

We'll come back to the idea that individual spaces are better suited for some games more so than others when we introduce Barricade, which is a staple of our game library, as well as the foundation on which many of our game variations are built. It is a rock star of the theatre game world because it requires focus, concentration, and absolute, utter silence (down to nary a squeak from the floor), and yet campers are constantly begging (yes, literally begging) to play it.

But before we get there, we're going to quickly cover some basic definitions that you'll see bandied about in all of our game descriptions. They may seem simplistic, but having specific definitions to use when facilitating games can be the difference between a success and a Recess-type scenario in which the kindergartners take you as their hostage.

The active parties in camp:

Campers: "Campers" are the youths who make up your class. Though they are essentially students, and their reason for being at camp is to learn, being identified as "campers" helps to separate theatre camp from school. (If you are an intrepid educator playing these games in your classroom, "students" is probably more appropriate.) Also, most students want to be treated as grown ups, so addressing them as "campers" allows us to refrain from referring to them as "kids" or "children."

Players: "Players" are the campers playing the current game or activity. They are the protagonists...the heroes...the subjects...of the stories that unfold in the game. Every single experience within a game should be tailored to the growth of the players, but that doesn't mean the players always win.

Teachers: "Teachers" are the primary facilitators of camp and usually the adults in the room. Teachers sometimes can be players, but always with the objective of providing a growth experience for campers...

Andy's Story Time!

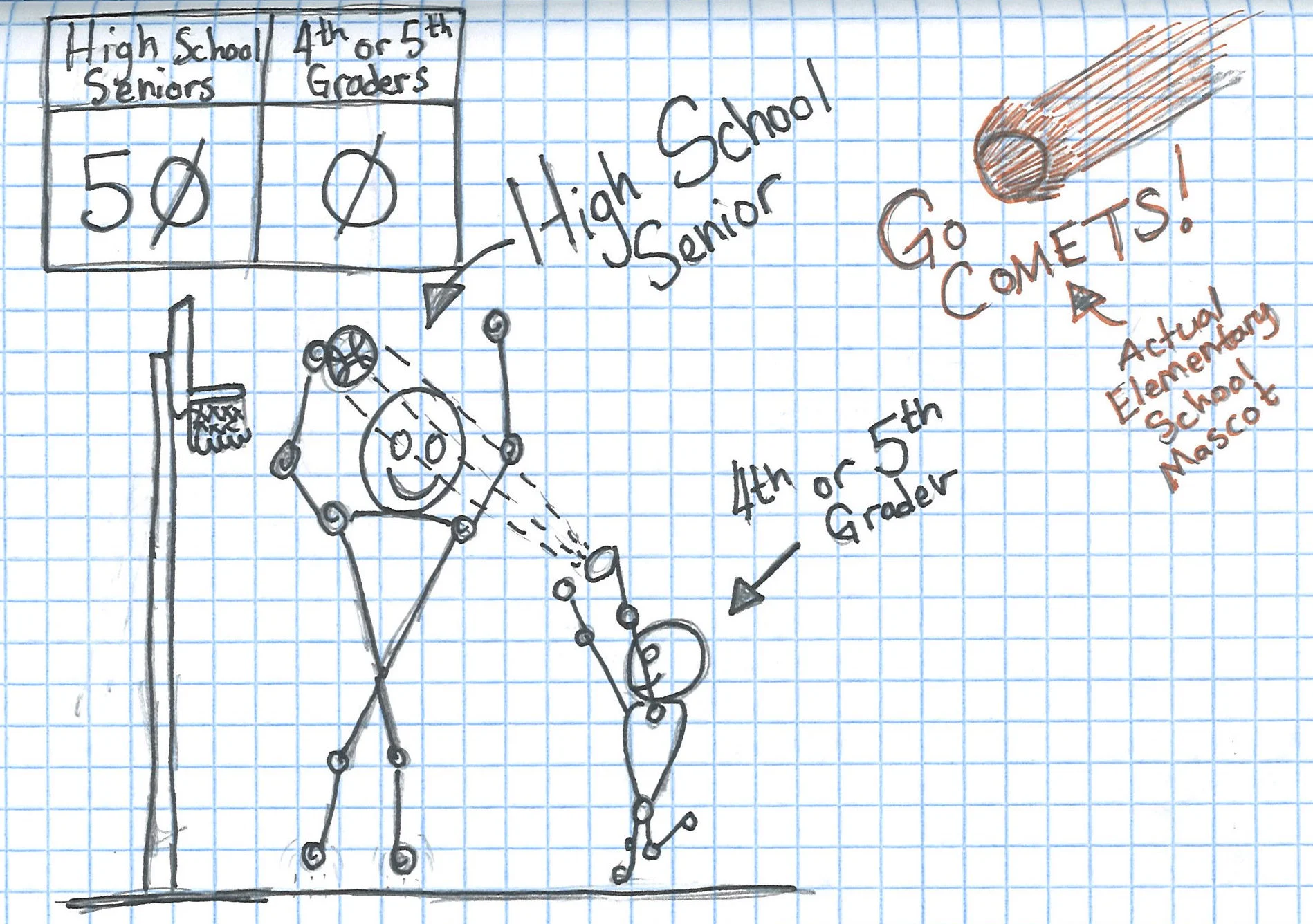

In high school, I participated in a pen pal program with students who were currently attending the same elementary school I had. I wrote letters back and forth to a specific upper elementary student for a year. Before graduation, we were invited to come out and spend a few hours with them. We got to see their favorite parts of the classroom, and the visit also happened to be scheduled during a recess break. So, of course, this clearly meant that the high school seniors (most of us legal adults) had to play on the playground with the elementary school children (most of whom were not legal adults).

My group of friends decided to play a game of basketball with our pen pals. It seemed only fair that it should be us (the legal adults) vs. them (mostly 4th or 5th graders). The elementary students seemed amenable, and since none of us high schoolers were very sports inclined, we thought the shorter basketball hoops would really help us out.

Needless to say, this didn't end in the best way. We mercilessly annihilated the elementary school kids, throwing long shots, dunks... and other totally tubular basketball stuff. We blocked their shots, stole the ball, and otherwise exploited our advantage.

Looking back at how much my high school self enjoyed heartily beating a group of elementary students at basketball, I really think about what the experience was like for them. Yes, they enjoyed hanging out with high schoolers, because everyone knows that high schoolers are cool, but we weren't really great vanguards. We were, however, the only undefeated high school team playing against elementary students in Boone County's history.

...so it is important to keep the objective of transferring skills and knowledge to players as your highest priority if you choose to participate in a game.

Side note for another day: This is a culture that we have to actively cultivate within the youth theatre, because we often operate as a one-room theatre schoolhouse, in which kindergartners are playing a game alongside high school seniors. This can be heartwarmingto observe, but it can be a delicate balance to keep tears coming from the teachers and not the kindergartners - more on that another day.

Judges: Teachers also usually act as "judges." They are the eyes and ears that keep the experience as balanced as possible for all players. They must find a happy medium between providing appropriate challenges for players and giving students the best fighting chance to be successful.

Activities: "Activities" are structured to teach specific skills related to performing (diction, projection, character development, physicality, etc.). The teacher may have goals in mind for what successful completion of the activity looks like, but there isn't a way for students to objectively "win."

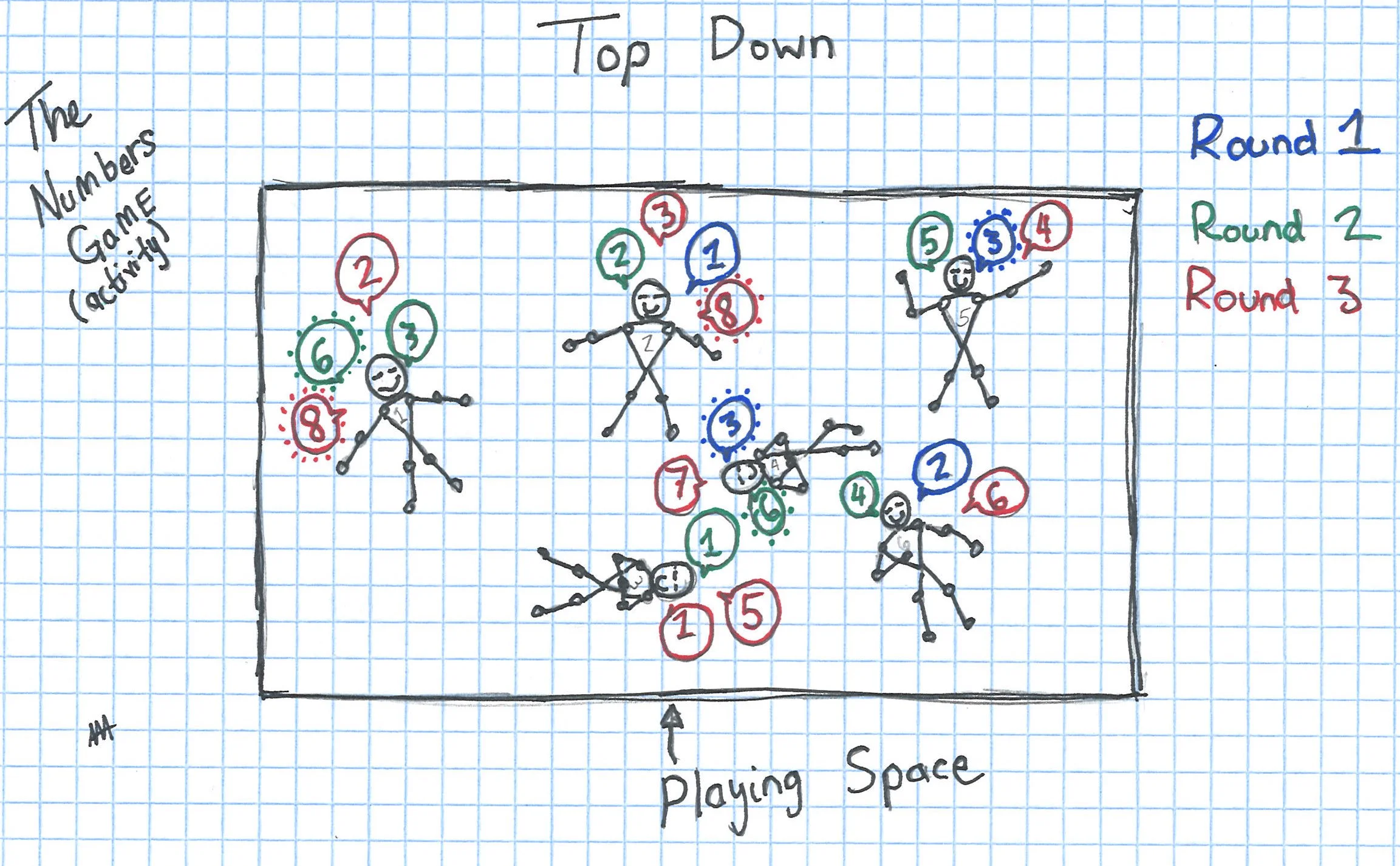

A great example of an activity is "The Numbers Game" (which is actually an activity). Yes, this is immediately confusing, but hang on and don't panic! (By definition, theatre people don't like definitions.)

The Numbers Game:

Generic Brand Name: Coming to Terms with Unpleasant Adult Realizations

Goal:

1) Players understand that they will never have 100% control over what other players do in the game. By extension, they will never have control over the choices other people make in life. Spending time being frustrated will not help them be successful in the game or life.

2) Taking the time to listen and wait patiently will help them be more in sync with the needs of any group.

Explanation: The task is to count as high as possible as a group, with each player only allowed to say one number at a time.

Materials: None

Age Group: Old enough to count - Adult

Activity:

1) Instruct players to find a comfortable position lying down within the boundaries of the playing space. Once they get there, ask them to close their eyes. You can even dim the lights, if your students find it helpful.

2) Explain that their task is to work as a group to count as high as possible, but each player can only say one number at a time. Remind them that if a pattern starts to form, or you see players coordinating who will speak next, the group will start over. If a number is skipped, start over. If two people say the same number, start over.

3) Allow the group to experiment with these restrictions for at least 4-5 tries. Usually, players reach the 7,8, or 9 range, then get stuck and frustrated with the experience.

4) When this occurs, take the opportunity to go through a deep breathing exercises.

Instruct players to:

- Place one hand on their belly, just below their ribs, and the other on their chest.

- Take a deep breath through the nose, and let the belly push the hand away.

- Exhale the air out through pursed lips, as if blowing bubbles through a straw. Encourage them to push the air out over a longer time than normal by counting down from 5. Ask them to notice the hand on the belly going in as they exhale.

- Repeat this 3 to 10 times.

5) Try the counting activity a few more times, starting over at 1. Set a goal the group is trying to reach: 20 is a good place to start.

Tricky teacher trick: Students will probably think that the breathing exercises are to help them clear their heads and regain focus to try the activity again. And they 're partially correct. But by breathing together, they also are syncing up heart rates and thereby internal counting speeds, actually making the task more difficult. Sometimes players will come back from the deep breathing and make it to a higher number than before the break. Sometimes they won't. That's not really the goal of the activity, but it's important to discuss in the debrief.

Debrief:

All of our games and activities end with a debriefing session, based on a few simple questions:

1) Were you successful? What went well?

2) What was challenging? Why? What could be changed to make it less so?

In the case of "The Numbers Game," wait to introduce the goals for the activity until after you have played and students have had a chance to share their impressions and thoughts. More than likely, one of the challenges they will mention is the frustration of waiting for a long time to say a number, only to have someone else say that number at the exact same moment. When it becomes apparent that there is no foolproof solution to avoid this issue in this scenario, make a connection by asking, "How does that apply to your school day?" (Or to the play we're rehearsing? To life in general?) From this discussion, see if students feel there is value in an activity like "The Numbers Game. What can they practice or learn from it?

Retrofitting "The Numbers Game": Let's say you're looking for an activity that will illustrate the value of nonverbal communication. The Numbers Game could be very useful, but you would want to make some changes to the restrictions and set up. Rather than having students lie down, you might have students sit in a circle with the lights on. If you see players organically begin to use subtle nonverbal signals to coordinate who will speak next, encourage it. What happens if you assign each student a partner, and if either of them speaks a number, the other partner must speak the same number at the same time?

Games: "Games" are constructed to have clear, winnable objectives. The objectives can be reached as a team, individually, or both. The validity of games as teaching tools is just as high as for activities, but it all ties back to what your goals are as an educator (a phrase you will hear a lot from this guide).

Barricade

Barricade:

Generic Brand Name: Border Crossing (if you'd like to add some political flair)

As previously mentioned, Barricade is a favorite game for both campers and teachers. It's ideal because it's quiet, yet active. Andy learned this game from a charming theatre company called CLIMB in Minneapolis, and there are probably many other versions out there. We use Barricade as a modifier for playing completely different games, using the phrase "barricade rules" (meaning they must complete the task in total silence) to add another layer of challenge.

Goal:

1) Players must exercise control over their bodies in order to cross the barricade. Actors need to have control over their bodies so that they can interact convincingly with others on stage, but it's also an important skill for all human children as they interact in their daily lives.

2) Players practice total silence while crossing the playing space, just as actors must do between scenes in a production.

3) Players who become part of the barricade must use strategic thinking to keep other players from crossing successfully. Players trying to cross the barricade must use strategic thinking to navigate around it.

Explanation: Players must cross from one safe zone to another without making noise or touching any part of the barricade.

Materials: A large, open space, with room for safe zones on either side. A floor with a tendency to squeak is ideal. (The stage at the Daily is ideal for Barricade, which is probably why it's become one of our signature games. It has plenty of creaks and squeaks, and not always in the same places. I've facilitated this game in other spaces, and it's never quite as successful. For more info on what to do if you don't have access to a suitably squeaky floor, see "Retrofitting Barricade.")

Age Group: K-Adult

Group size: 10+

Activity:

1) Define the space as two distinct sections: the main playing space, where Barricade rules are enforced (no noise), and a safe zone on either side. Make sure the spots that mark the transitions into the safe zones are easily identifiable (a masking tape line, a strip on the floor, etc.).

- At the Daily, the wings are the safe zones, the apron is out of bounds, and so is the upstage wall.

2) Ask your players to head to either of the safe zones. Make adjustments so the two groups are roughly the same size.

3) Explain that their mission is to cross the playing space without making an iota of sound. The game is split into rounds, and a round consists of crossing from one end of the stage to the safe zone on the other side. Instruct that when they reach the opposite safe zone, they must wait until everyone is finished crossing for that round. You, the judge, will tell them when the next round begins.

4) Let them know that you will be the judge of who has crossed silently and who has not. If you hear a player make noise, you will tap them on the shoulder or speak their name. At this signal, players must freeze immediately in their spot until the round ends.

5) Instruct players to begin by saying, "When you are ready, you may cross the barricade."

6) As the judge, you may move throughout the playing space, listening for any sounds made by players. And we do mean any sound - coughing, clothes rubbing together, shoe noises, the aforementioned floor squeaking - anything. In order to be successful, players will realize they need to move more slowly than normal, but if the round drags on too long, you can say, "You must cross the barricade in 10, 9, 8, 7..." and any players still in the playing space when you reach "Freeze" become part of the barricade.

7) At the end of the round, give the frozen players the instruction to "join the barricade." This means that these players will act as a blockade by spreading out across the playing space. They can stand individually or connected like a chain link fence, but they must remain completely still. Give the barricade about ten seconds to form (silently), then remind remaining players that they may not touch any piece of the barricade during the next crossing, or they also will become part of the barricade.

8) There are two paths to victory in this game: 1) the last surviving player is the victor, or 2) the barricade is able to stop all players from crossing, and the barricade wins. Play until one of these happens.

Notes: If you are playing with a group smaller than ten, or in a really big space, you can use chairs, music stands, desks, set pieces, curtains, basically anything you can think of, to create a portion of barricade that is used in the first round. This also works well in spaces where the floor is not creaky.

Debrief:

1) What went well?

2) What was challenging? Why?

3) Why do we play Barricade? How can it apply to theatre?

Retrofitting "Barricade": We've created a ton of different versions of Barricade, including one in which players must cross the barricade while attached to a partner, barricades with moving pieces, and a version called "Raptors in the Kitchen," which, of course, gets its name from the iconic scene in Jurassic Park. In this version, raptors (teachers and/or teen interns) try to tag players (with foam swords...it's not a perfect metaphor...) as they move through the barricade. We've flown in curtains to create a maze and placed raptors throughout the maze, and we've even played using a web-cam as the "eye" of the judges. In this version, the players are allowed to make noise, but if the judges see them, they become part of the barricade.

Is Barricade a staple in your youth theatre program? Tell us about your version in the comments! Also, let us know if you have any questions before giving either Barricade or The Numbers Game a go with your group!