Issue #2 - The Life of a Triangle

Who doesn't love a good circle? King Arthur sat at one to avoid the narrative that the king was the head of the discussion and to symbolize that his knights' lives were valued as much as his. Flying saucers, the One Ring, doughnuts -- all brought to us by circles. They're the best shape for sitting as a group -- everyone can see everyone else, and there is just something comforting about a shape with no beginning or end. Circles have many outstanding qualities, but they sure can muddle a narrative.

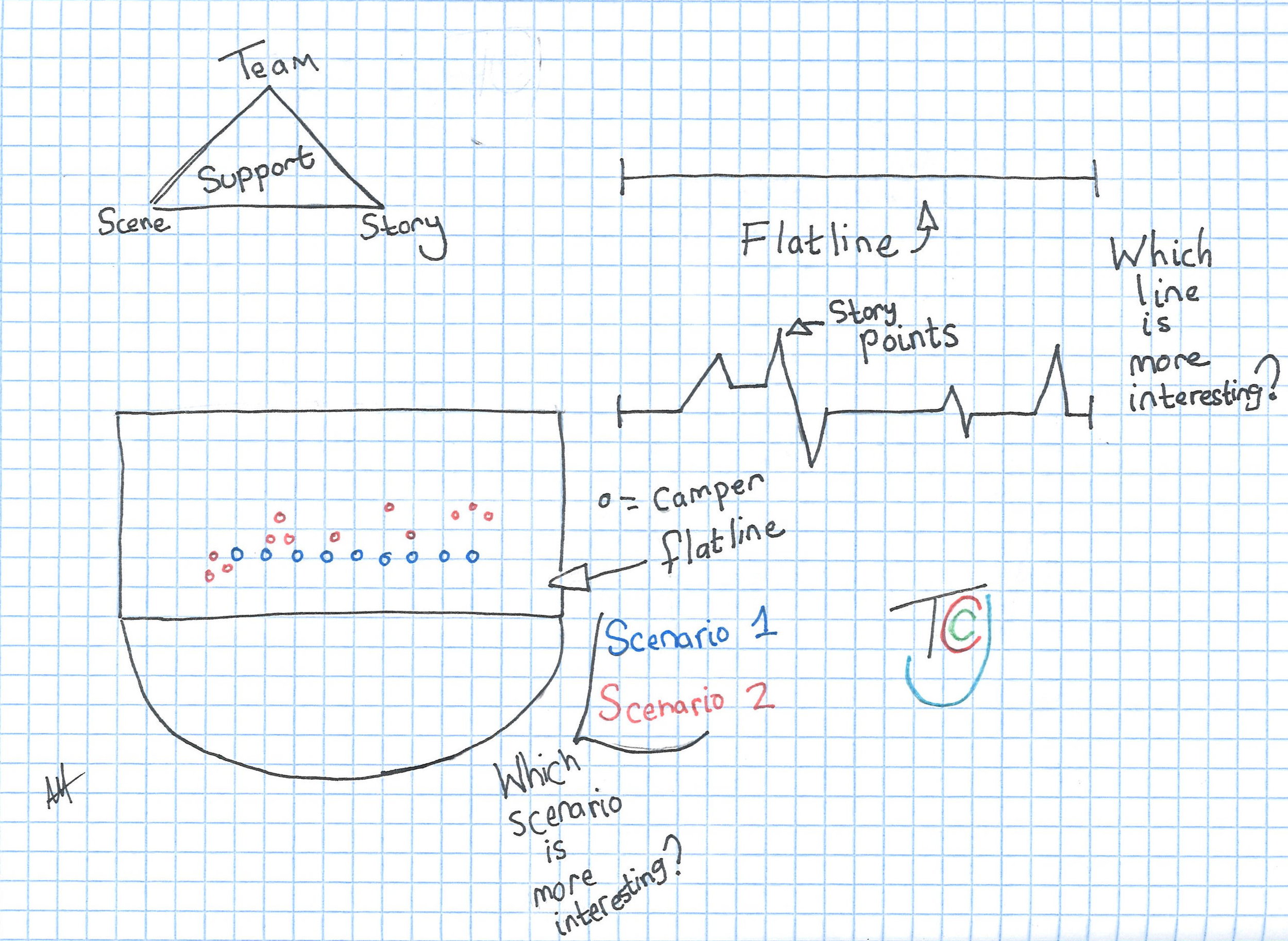

This is where the triangle can really shine. They are the naturally occurring geometric shape of the theatrical world, both in its physical structure and philosophical nature. (And yes, math lovers, we've heard that circles can be broken down into triangles and triangles contain circles - the Reuleaux triangle, congruency, math words...P.S. We'd love to develop a geometry lesson plan using stage picturization to illustrate these concepts...but first we need an intrepid math educator to help us understand them!)

But back to triangles: they are an excellent way to organize blocking on stage to make the action visible to the audience, and a solid model for organizational structure. Andy often tells campers that a triangle is the strongest geometric shape, because all sides support each other, and there is little space for the sides to buckle. I'm not sure if that is a scientific fact, but it is at the very least a probable alternative fact.

The first symbolic triangle we'll tackle here at TCCG is the core of our theatre philosophy. From day one, we ask campers to:

Support Your Team

Support Your Scene

Support Your Story

Support Your Team - Collaboration is the key to success in theatre. There is no way to avoid it, and under-valuing it can be disastrous. It takes all sorts of skill sets to put up a show, so encouraging students to count lines and referring to them as "stars" will do nothing but create "me-focused" individuals. Your job as an educator or director is to create a TEAM.

Teamwork is a supposedly simple concept, but describing its chemical makeup is an elusive task for students (and most adults). Campers know adults like that word, so they will use it to vaguely answer questions about working successfully as a group.

Example:

Teacher: How can you support your team?

Student: Teamwork!

Most of the time, adults will accept "teamwork" as a valid answer to this question, but what concrete information does that really give students? Instead, when you get that word thrown at you, take the time to dig in with your students and create a definition for it. There probably is no "correct answer," but the lazy answer is "working together as a team," because that only restates the phrase "teamwork."

Example:

Teacher: How can you support your team?

Student: Teamwork!

Teacher: (Restates question using student's answer) How will I be able to see that you're working as a team when I look over at your group? What will you be doing?

This will hopefully elicit answers like: "We're taking turns talking," "Everyone has a job to do," "We listen to everyone's ideas," and "We vote to make big decisions."

Support Your Scene - We use this phrase as a reminder that each performer should know the focus of the scene - where the audience's attention should be - at any given moment. That way, if the performer is part of that action, they can work to make it seen and heard. If they are not, then the goal should be to add to, not distract from, the moment. In some ways, "Support your scene" also ties in with "Support your team" - for example, if students are talking while a teacher is talking (but that probably never happens to you).

A great way to illustrate "Support your scene" is to ask 2-3 students to perform or improvise a scene. Join in as supporting character. As the students begin to speak, begin to model different ways in which an actor could be distracting from the scene. These will depend on your students' age and experience: you could whisper to other supporting characters, stand fidgeting and staring off into space, wave to the audience, or even perform an exquisite pantomime in which your character experiences a profound realization about the meaning of life while buying a loaf of bread. Still, none of these actions support the scene.

Then, go back to the beginning of the scene, and this time, model a character reacting to the characters who are the focus of the scene. After the scene is finished, ask the students who were watching what was most memorable about the first version of the scene. The second? Ask questions that require students to verbalize the difference between the two, and discuss and model how you can support a scene in which you do not have any lines.

Often, the issue of being seen and heard is addressed with rules like "never turn your back to the audience." In our book, these rules are pretty flimsy. While they offer a great starting place, sooner or later these rules will need to be broken. Sometimes, it could be a much greater advantage to hide part of your action in order to build mystery. Or you could be directing in an arena-style theatre, so actors always will have their backs to different portions of the audience. A more effective method is to start by identifying the focus of the scene and simply block the rest of the action around it.

Support Your Story - The meaning of "Support your story" can vary depending on the focus of the group. In a Building camp, where campers write their own material, "Support your story" can be a reminder to inject their scripts with conflict and action, or in a more traditional sense, it can mean that actors must accept the "givens" that make their character's world tick. They can ask all sorts of questions and decide it's utter nonsense, but while they're acting, they must accept these givens as truth.

The Flatline:

The flatline illustrates both a theatre philosophy and the physical structure of a scene. A flatline beautifully represents the need for ups and downs in a story arc andlevels and depth in your physical blocking. If either of these are flat, it means whatever you're doing is dead. This is just as true on stage as it is in a hospital.

In writing, the more story points you have (within reason), the more "alive" the story is. Think of aroller coaster or the 5-point story diagram we all learned in school. When it comes to blocking actors' physical movements, you can use the same principle. Putting your performers in a simple straight line is boring, and it kills your action on stage. Everyone is equal, so no characters are important (Earlier, we said a circle can really muddle a narrative. So can a line.). Thus, the audience doesn't know where to look, and you can't progress the story. Arranging your performers in triangles will add depth and keep your scenes "alive."

Show and Don't Tell:

Theatre is a visual art form -- it should be approached from a visual point-of-view. Always find a way to show what the audience needs to know -- don't depend on dialogue to communicate it. We start teaching this important concept in an activity called "The Magic Ball."

ACTIVITY!

The Magic Ball:

Generic Brand Name: Charades for the Poors

Goal:

1) Use and polish basic pantomime skills.

- Pantomime: Express or represent something by extravagant and exaggerated mime.

2) Practice supporting your team by performing pantomimes clearly so that the objects will be easily guessed by teammates.

Explanation: The invisible magic ball is passed around a circle, with each student reshaping it into a different object and pantomiming using it. Other students try to guess what the magic ball has become.

Materials:None (are you sensing a pattern with this category?)

Age Group: preK-Adult

Group size: 2+

Activity:

1) Gather your group in a sitting or standing circle.

2) Introduce the magic ball. For best effect, make sure that you pull the magic ball out of your pocket, or a box, or a camper's ear - the magic ball doesn't simply appear.

- The magic ball should have the size and weight of about a baseball or softball. The devil is in the details, so the more information you show, the better.

3) Remind campers that the magic ball does not adhere to our world of physics: "When I throw this ball in the air, it stays in the air until I let you know it is coming down. How do I let the audience see it's falling?"

- (Usually, the answers we get are a description of what we do when throwing the ball in the air and catching it, but the biggest detail is overlooked)

4) If students are stuck, try to break down the action of catching a ball - "What are step-by-step directions for catching a ball?"

- (Again, there will be a lot of simple answers like "Use your hand," but the answer you are looking for is "You have to see it to catch it.")

5) Since your physical movements usually depend upon what you see, when you throw the ball up, it doesn't come down until you see it come down.

- This is the cardinal rule of pantomiming. YOU NEED TO COMMIT TO YOUR ACTION. If you don't believe it, nobody else will believe it either.

- Or, as Captain Obvious once said, "'Act' like it is real."

6) After setting up the physics of the magic ball, take a brief moment to mold it into a different item and use it.

- We like to use a frisbee or a boomerang because they require very clear motions.

- Don't dwell too much on the molding, because students will spend 2 minutes molding very intricate details and 5 seconds using the item. The goal is for the action, not the molding, to give the item's identity away.

7) Ask students to guess what the magic ball has become. Remind them that their task is to be so clear in their pantomime that everyone can guess. It is NOT to dupe them. This goes back to building supporting your team.

8) Return the magic ball to its original form and weight, and hand it to the next player. One by one, campers will reshape the magic ball into an item and demonstrate its use (shooting a bow and arrow, casting a fishing line, brushing your teeth).

Debrief:

1) Which objects were easy to guess? What did those players do to make it easy for you to guess?

2) Without naming objects that were difficult to guess, what made guessing hard?

3) Why do we play Magic Ball? How can it apply to theatre?

What are your favorite activities for teaching pantomime?